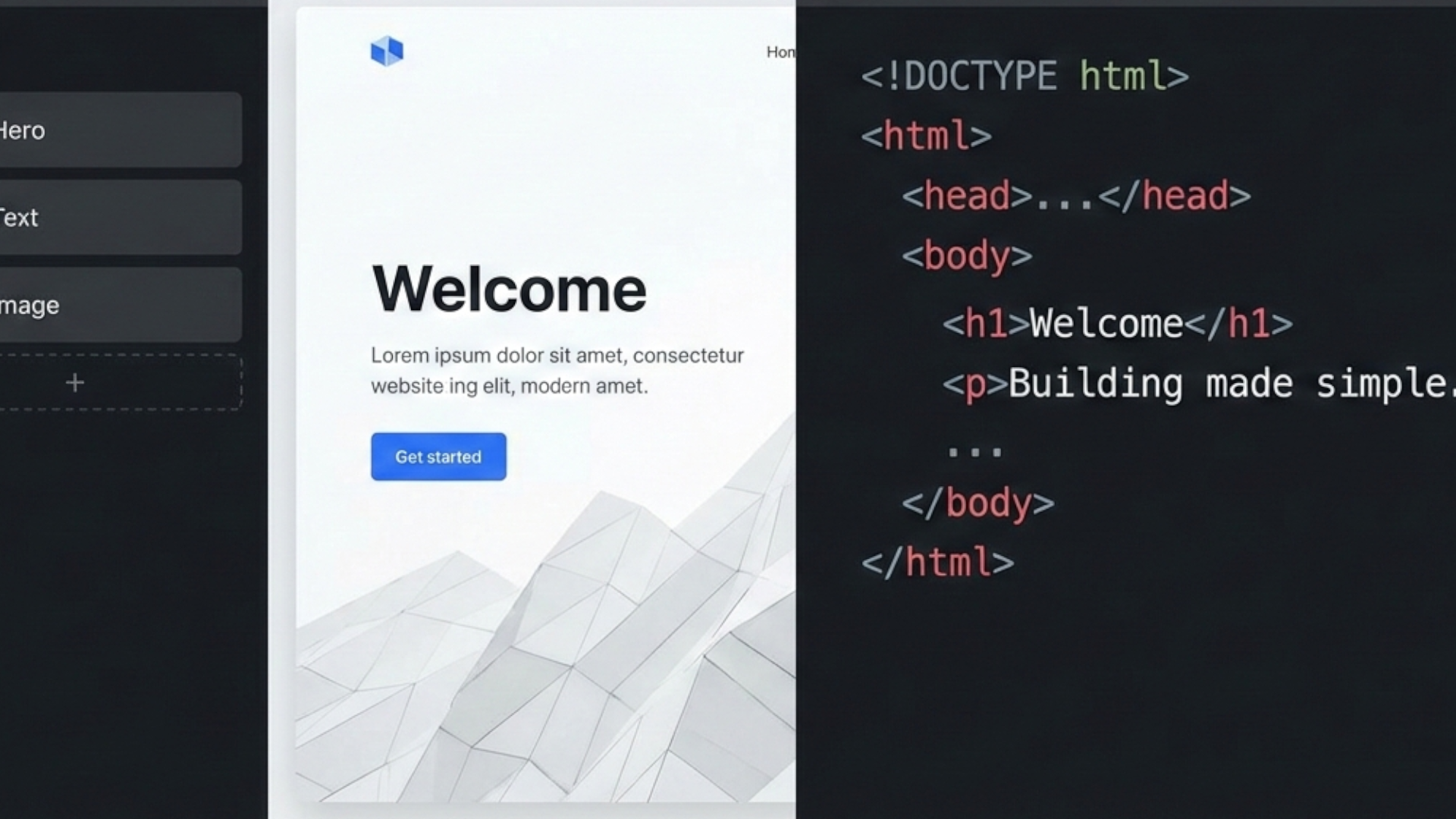

From Hardcoded Lists to JSON Files: Giving Flask Apps Real Data | Python Comeback Journey #8

Up to this point, my little Flask app had been running on hardcoded data — a list of books sitting directly inside app.py. It worked fine, but something about it felt wrong. Each time I wanted to add a new book, I had to edit the source code, save, and restart the server.

That’s not how real apps behave. Real apps load data dynamically.

So I decided to move my book data into a JSON file, and this simple change taught me more about data handling than I expected.

🧩 Step 1: Moving the Data Out

Originally, my data lived right inside the code:

|

1 2 3 4 5 |

books = [ {“id”: 1, “title”: “The Great Gatsby”, “author”: “F. Scott Fitzgerald”, “status”: “Completed”}, {“id”: 2, “title”: “1984”, “author”: “George Orwell”, “status”: “To Read”} ] |

I moved this into a new file inside a data/ folder:

|

1 2 |

data/books.json |

|

1 2 3 4 5 |

[ {“id”: 1, “title”: “The Great Gatsby”, “author”: “F. Scott Fitzgerald”, “status”: “Completed”}, {“id”: 2, “title”: “1984”, “author”: “George Orwell”, “status”: “To Read”} ] |

Now, app.py no longer stored any of the actual data — it just loaded it.

⚙️ Step 2: Loading Data with json.load()

Inside the route, I replaced the hardcoded list with:

|

1 2 3 4 5 |

import json with open(‘data/books.json’, ‘r’) as f: books = json.load(f) |

json.load() turns the file’s contents into a Python list of dictionaries — the same structure my app was already using.

Suddenly, the app became dynamic. I could edit the JSON file, refresh the page, and see the changes instantly.

🧠 Step 3: Understanding open() and File Modes

To make this work, I had to understand the role of 'r' in the open() function.

'r' means read mode — open the file to read its contents but not modify them.

Later, I learned that 'w' overwrites a file (used when saving changes), 'a' appends new content, and 'r+' allows both reading and writing. These tiny letters are small but mighty.

They taught me that file operations are explicit — Python doesn’t guess your intentions. You have to tell it exactly what kind of access you want.

📚 Step 4: Writing Back with json.dump()

When I eventually needed to modify the list and save it again (like adding a new book), I used:

|

1 2 3 |

with open(‘data/books.json’, ‘w’) as f: json.dump(books, f, indent=4) |

The indent=4 makes the output neat and readable, which matters when you’re managing data manually.

💡 Step 5: Reflection

What started as a small refactor became a major turning point. Moving data out of the codebase introduced a new layer of separation — logic in one place, data in another.

It made me realize that managing data is really about managing change. Code changes should require redeploying the app; data changes shouldn’t.

And JSON, with its simplicity, was the perfect stepping stone toward databases.

Next up, I’ll take the idea further by learning how Flask handles form submissions — reading user input, saving it to JSON, and creating dynamic updates.

Stay tuned for Python Comeback Journey #9: Creating Forms and Handling POST Requests in Flask.

Leave a Reply